Shrujan: Stitching Communities

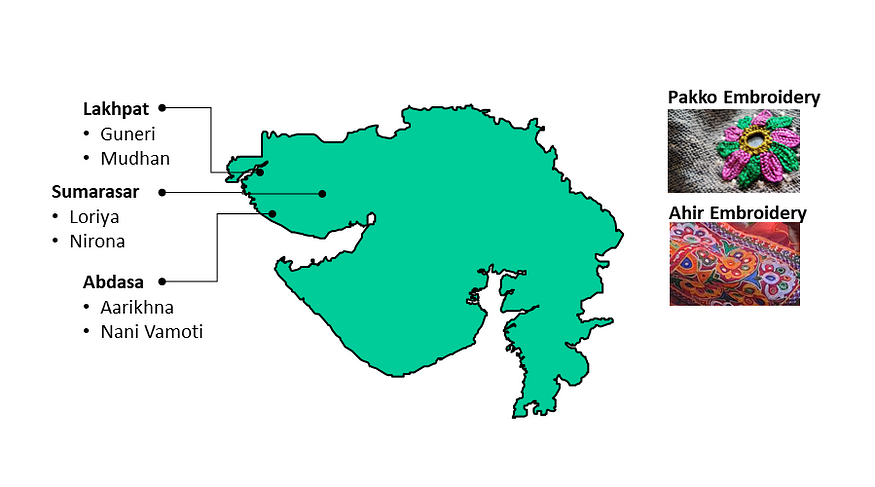

We had previously written about the market access conundrum, and how market access is a daunting challenge that rural women have to face. To explore how this challenge was being addressed by the artisan community in Gujarat, we spoke to 60 artisans from six villages across Kutch earlier this month. Each village is home to communities who specialise in a unique form of embroidery. These artisans are connected with Shrujan, a not-for-profit committed to preserving the unique forms of embroidery practised by communities in Kutch.

Having worked with Kutchi artisans — whom they have placed at the centre of their work for over 50 years — the Shrujan team has developed a deep understanding of the region and its people. Given that women in most of these communities are not allowed to leave their villages for higher education or work, Shrujan brings work to them — as ready-to-use kits[1] that contain all the raw material required to make the finished product (fabric with reference markings, needles, and threads chosen carefully by Shrujan’s design team).

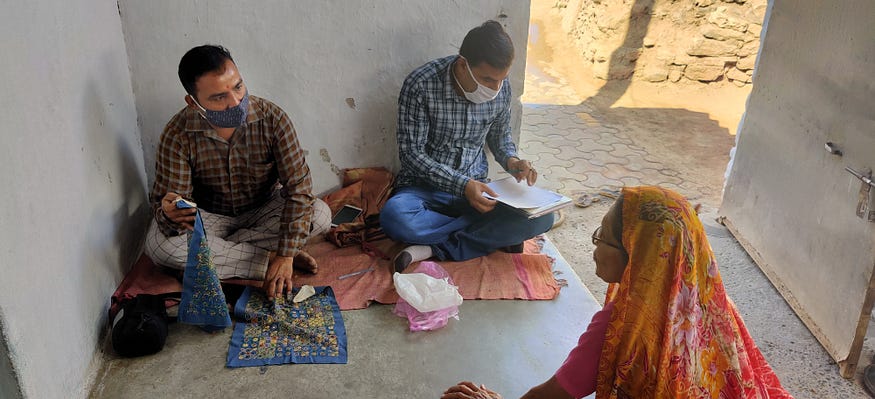

Artisans have the flexibility to work as much or as little as they like. For most, embroidery work provides supplementary income over what farming brings in; nonetheless, it is spent on household expenses. The Shrujan team visits these artisans for quality checks and collection of the embroidered product — it could be a patch that may take a few weeks to complete, or a saree, given to only the highest performing artisans, and can take over a year to complete.

Shrujan’s production team members visiting the artisan’s home for quality checks and collection

Shrujan’s production team members visiting the artisan’s home for quality checks and collectionShrujan currently faces two challenges. The first is that the approximately 3,500 artisans in its fold are scattered over 140 villages in Kutch. This poses a challenge to operationalise its highly involved production process and makes for a significant portion of its production cost. The second is the palpable fear that systematic transfer of knowledge of embroidery and stitching styles to newer generations of women may not happen. Shrujan has identified 40 plus embroidery styles in the 12 communities it works with, and each style has its own unique stitching methods and motifs. The current generation of women comes from households already economically empowered by its previous generation of women artisans, and may be less inclined to keeping this craft alive.

These challenges are not unique to Shrujan alone, and are faced by several other organizations that work with rural women artisans. In our upcoming report, we delve into use of mobile phones, and where in the supply chain (with the artisan, with the organization, or both) can they be placed to mitigate the severity of these challenges.

Endnote

[1] Shrujan’s process of making these kits ready to be sent to the artisan is an extensive process, deserving a blog post of its own. The process involves several steps- it is akin to a well coordinated orchestra, where the design team and the production and logistics team move in perfect tandem to ensure that the finished product would cater to the market’s taste, capitalises on the artists’ capabilities, and preserves the heritage of the artisans’ community.

This research was developed as part of the Bharat Inclusion Research Fellowship.