People of Bharat: Vinay, Ahmedabad

Vinay and his family pore over a fat bunch of pictures; his uncle withholds the bunch and passes each photograph around for everyone to cherish closely. “These are from my wedding,” Vinay explains. His young 17 year old wife, Hema, sits across from us with her sari covering her face, indicating the presence of an elder. “We were married earlier this year. The photographs have just come,” Vinay continues.

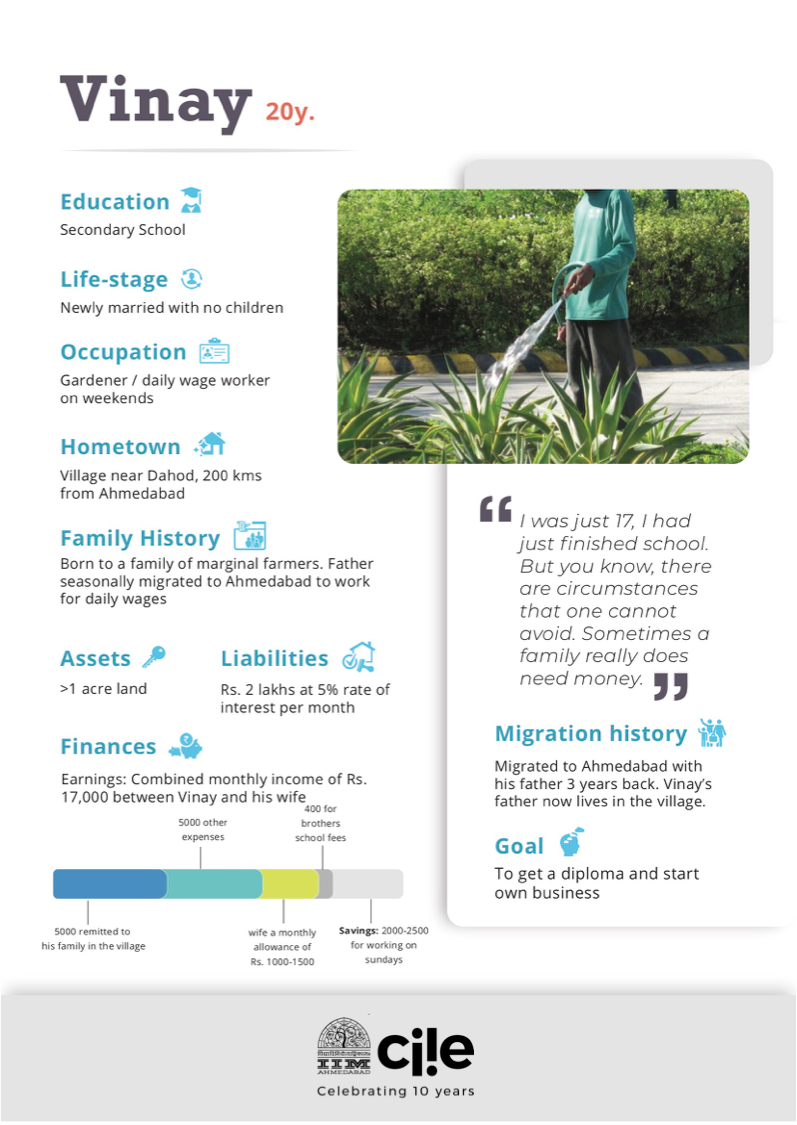

Vinay is a mali, a hired gardener at a big, neatly curated property in Ahmedabad. It is a 9–6 job that involves trimming, raking and watering the lawns, and planting and tending to the saplings. He works on the site with five other members of his family- his wife, uncle, aunt and grandfather. His aunt and uncle have a four year old, who follows Hema around and imitates her as she goes about her duties. She indulges him. He makes her laugh. She plucks grass moodily and keeps to herself when he isn’t around.

Vinay and I sit in the shade at lunch hour, while his family surveys each wedding photo for detail, attractiveness and memory. Vinay and his family are from a village near Dahod, about 200 kilometres from Ahmedabad. Vinay has lived in Ahmedabad for 3 continuous years, during which his visits to Dahod have been limited to weddings and festivals. Members of his family have visited him more often, looking for work in the city from time to time.

Vinay remembers his early experience in Ahmedabad. He had never left the village before. “I was with my father the first time I came here. He had done this for many years. He would come to the city, live here for work and send money home for us.” Vinay accompanied his father for the first time after he finished school. He had never had a job before and did not look forward to one eagerly. “I was 17, I had just finished school. But you know, there are circumstances that one cannot avoid. Sometimes a family really does need money.”

Vinay and his father took a 7 hour long bus ride to the city, leaving his mother and younger brother behind. At the city, his father would take Vinay to the labour naka every morning, where the two would wait for some contractor to pick and hire them for the day. “We did various odd jobs, depending on which contractor picked us. I worked at construction sites several times, and did night duties…” Vinay recalls.

One morning at the naka, Vinay and his father caught the eye of the contractor in charge of the current property on which they work. He offered them a regular job, with fixed monthly wages, putting an end to their daily job search routine.

Vinay and his wife live in a small rented tenement at a slum on the far side of the city. Members of his immediate family, at this instance, his grandfather, share the tenement during their visits. Vinay’s uncle and aunt have different quarters. The daily commute from home to work takes Vinay and his wife about an hour each day. The couple is up by 6 am, and queues up with plastic ‘drums’ at the nearest community water tap. Morning chores take about an hour. Hema manages to cook and pack lunch for the day. The couple leaves home by 8 am.

Vinay finds that they are on good terms with the contractor. He is prompt with making payments. Each garden worker is paid Rs. 7,500 a month. Each workday is accounted for. Vinay and other garden workers are expected to work six days a week; all absences incur pay cuts.

I ask Vinay if Hema earns the same wages as he does. He responds saying, “Yes, we all make Rs. 7,500 each.” But Vinay’s employer does not pay Hema directly. Instead, he cuts a combined cheque of Rs. 15,000 and hands it to Vinay at the end of each month.

“I immediately give her an allowance, as soon as I get my hands on the money. Say Rs. 1000 to Rs. 1500 for anything she may want to spend on herself. But yes, I decide what to do with the rest of it”, Vinay emphasizes.

Most of the money is marked even before it arrives. Vinay usually en-cashes his cheque the very next day. He transfers Rs. 5000 to his family back in the village. “They have to pay for my brother’s school fee. It is Rs. 400 a month. And there are other expenses, so I transfer at least Rs. 5000 every month”.

Vinay’s father no longer visits the city for work. “Somebody has to stay back, as all the other men are away, looking for work”, Vinay points out. “My father works on the farm and my mother helps him. We do two crops a year, maize in the monsoons and chick pea in the winter. Summers are too scorching to go looking for work, hence everyone stays back at home” he continues.

Vinay’s family- his father, mother and younger brother were left with about an acre of land after the division of property within the larger family. He claims that there is little money in farming and that they just about manage to recover costs and meet basic consumption needs from farming.

He explains, “You see, for instance with corn, we put in 10 kilograms of seed, which comes for Rs. 1300 a quintal. By the end of the season, we reap about 4 quintals. But prices plummet during the harvest season. So we end up selling at a big difference per quintal. Then there is the cost of hiring a bull and other inputs. There is barely any money to be made”. Vinay prefers the village life, the familiarity and the quiet comfort of it. “But I cannot live there,” he says, “there is no steady income.”

Back in Ahmedabad, Vinay tallies up other expenses. The couple parts with almost a third of their leftover wages, Rs. 3500, in paying for house rent. Cooking fuel- kerosene, costs them Rs. 2100 per month. A couple of thousand rupees are spent in groceries and other essentials. By the end of the month, the couple manages to save Rs. 2000 despite their tight finances.

“I save each month and deposit the savings in my bank account” Vinay shares. Vinay has devised other means of saving money apart from carefully budgeting his income from garden labour. “We don’t have to work here on Sundays. So, Hema and I go to the naka on Sunday. Over four weeks, we make between Rs. 2000- Rs. 2500 by working on Sundays each month. That money goes straight to my savings account,” he beams. He prefers to leave his savings in the bank account. FDs and RDs block his money. It is easier to transfer money in case of emergencies when he has cash in his account. He sometimes uses the remittance app to make transfers to his father’s bank account.

“But, regardless of how I save, I desperately need to save, that is the whole reason why I am here”, Vinay shares. Thinking back to the first time he arrived in Ahmedabad, Vinay recalls, “We were under huge debts with money lenders back in the village. My father had borrowed money to rebuild our house; and my coming here to work was the only way we were going to pay off those debts.” Between his father and himself, and now his wife, Vinay has covered much of the repayment. But the family is still saddled with Rs. 2 lakhs of unpaid loans borrowed at an interest of 5 percent per month.

“The interest is exorbitant. I try so hard to get a loan from the bank, but they refuse, simply refuse. They say my income is too little hence I don’t qualify for a loan. So, we have no choice but to go to a moneylender. Additionally, every year there is some wedding or ceremony in the extended family. We end up borrowing Rs. 20,000 — Rs. 30,000 from relatives every year. But thankfully, there is no interest on that money” Vinay narrates.

Vinay sprinkles broken spurts of English in our conversation. He tells me he has given himself two years to clear all debts and build some capital. “I am going to start my own business. I have not figured out what I want to do yet, but I do know that I am not doing garden work for long” he confides.

At the start of the year, Vinay considered applying for a diploma, but dropped the idea because he realized he needed to support his brother’s education instead. “I will do it though, at some point” he asserts, exuding confidence.

I look at Hema, listening in, half her face still hidden under her sari. “What about her?” I ask. Vinay does not seem to get my question. “She went to school” he says, “till class five” and smiles tenderly in her direction.

This research was developed as part of the Bharat Inclusion Initiative.