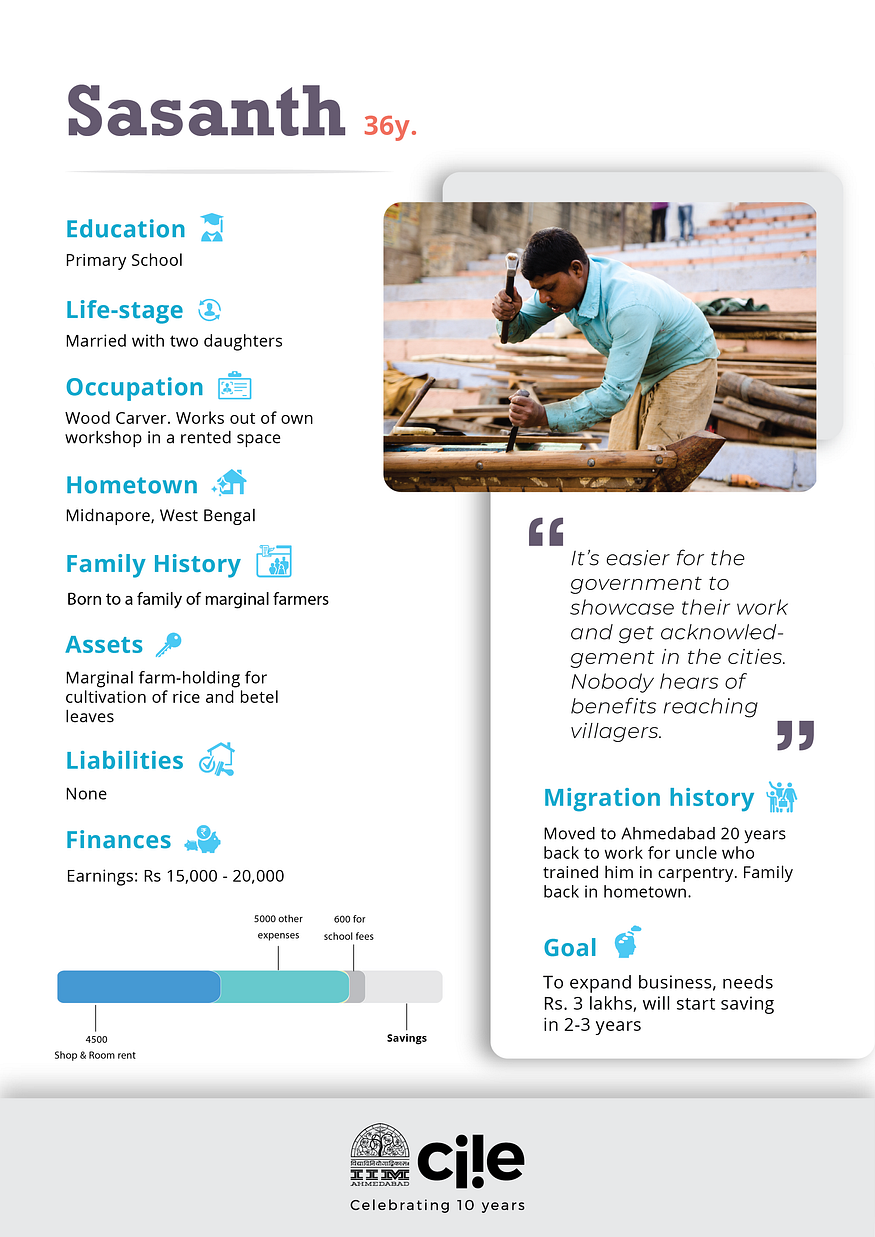

People of Bharat: Sasanth, Ahmedabad

I wander around one hot afternoon, looking for the shops where wood work is done. I know these shops; they are quite close to where I live. Usually, they are full of about 6 to 10 men busily hammering away, but this afternoon the shutters are down and I struggle to find a single store that is open for business. I finally spot one; with a lone carpenter in it, wiping his face with a thin, worn-out cotton towel. His face is the colour of earth, with deep furrows and lines showing. I find out later that he is only 36, but looks older with plenty of white hair peppered in his otherwise full moustache and beard.

I introduce myself and ask if I can sit down. It is too hot to stand and I worry that the beads of perspiration trickling down my back will dehydrate me if I don’t drink something soon. I ask him if I can get him a cold drink. “No madam. I just had lunch” he says. “Well, there goes my chance to have a drink”, I think, sitting down amidst sawdust and pieces of carved wood.

Sasanth Kumar Hajra hails from Midnapur district in West Bengal. His family consists of his wife and two daughters, his mother and his brother’s family, who all live together in a kachcha house in a remote village. They own a small piece of land, irrigated by means of a small pump, on which the family cultivates rice and betel leaves — earnings from farming keeps the household running. They do not own any livestock and do not intend to either. “These days village people do not keep cows or goats or chickens. It’s not done. It smells around the house — then nobody will give their daughter (in marriage to such a house)” Sasanth tells me. He adds with a hint of pride that he owns a fridge and that they cook over a gas stove in the village. He had done away with livestock when his wife came in.

Sasanth Kumar came to Ahmedabad almost 20 years back with his uncle, who trained him and taught him carpentry. He first worked at his uncle’s shop in Ahmedabad for a few years before renting a space for himself. He shares this shop with four other carpenters, who like him, left home and hearth to find work in the city. They live in a room behind the shop and share expenses on rent and food which amount to Rs. 18,000 each month-split four ways.

He charges for his labour; customers have to buy their own wood. He largely does carvings on wood. The current rate for wood carving work varies from Rs. 150 to Rs. 200 per foot of wood. He generally quotes a rate which is slightly higher or lower than the market rate; depending on the type of work (artistic or regular), on whether he is relatively free or busy, or according to the going rate at neighbouring shops (also in the same business) . “Sometimes I also charge based on what jewellery the client is wearing!” Sasanth says with a smile. He obviously knows his market. “Irrespective of the rate,” he says, “they (customers) all crib”.

Shop Work starts at 8 in the morning and the first shift is three hours long. At 11 am, the carpenters break for lunch. Sasanth goes to his room, cooks, eats and takes a nap. Then, he resumes work at around 2 pm and works till 10 or 11 in the night. He is not exaggerating. I have often seen these shops open and men working away, on my way home from late night dinners outings. The only break he gets is when he stops work to take a moment and chat with someone. Sasanth also takes up special job work from designers. For these, he charges per millimetre. Overall, he makes about Rs. 15–21,000 a month.

According to Sasanth, people have stopped appreciating wooden/carved furniture. “People don’t prefer carpentry for home furnishings anymore. They would rather buy ready-made articles….their finishing looks good on the outside but they won’t last for more than five years; if you drive a nail into a ready-made thing, it will not stay (put) because it is full of bhusa (sawdust).” Most of his orders are for temple interiors. He feels in spite of low demand for furniture, carpenters like him will thrive because, “people won’t stop building temples.”

Sasanth prefers to receive payments via cheque. He deposits cheques into his bank account whenever he finds time and his wife withdraws as per the expense needs of the household. Sasanth has no fixed income and is usually paid when the clients come to collect their orders.

I ask him if he likes doing what he does. My question irritates him. “Well I have to like it! Don’t I? What else can I do? I will have to do it as long as I can (manage)”, he snaps back. I feel for his constraints. He had already told me that he went to school only till the fourth standard. He really cannot choose to do anything else; except perhaps farming.

Sasanth shows me a printout of a photograph of two overlapping leaf designs. They were part of an assignment he took from an artist. He recalls that he made both components but realised he had made a mistake by not making one the opposite of the other. They did not overlap. “Mera nuksaan ho gaya (it was a loss for me)!” he exclaims and shows me the rejected piece of wood lying in a corner. I remark that his work is an art — a kala. He agrees. Interns from design colleges come to him to learn basic carpentry. They pay him a small amount in return.

I enquire if he gets any government aid. The government school in his village is free, I learn. His daughters study there. But he sends them for private tuitions and spends about Rs. 600 a month on their education. Last year, his eldest was hospitalised for 12 days. He spent Rs. 65,000 at the local private hospital. He feels government is of no help to villagers. “Jisko milna chaiye, usko milta nahi (those who are supposed to get {benefits} do not get them.)”, he ruminates. He thinks thats the government and politicians are more eager to help the urban poor. I ask him why. “It’s easier for the government to showcase their work and get acknowledgement in the cities. Nobody hears of benefits reaching villagers”, he responds. The other reason, he explains, is widespread corruption and bribery. He gives me an example. “Imagine I am a poor man and I am supposed to get a benefit of Rs. 2 lakh. (Then) I have to shell out 10 to 15 thousand as bribe (to the officer). I also waste 6 to 10 months following up. I (have to) keep asking ‘mera kaam hua kya?’ (Is my work done?) I might as well work and earn (that amount of) money in that much time.”

Sasanth owns a smartphone. It is useful since he can get orders on the phone and people can send him pictures of the artwork.

He manages a trip home every three months. A couple of years ago, he had brought his elder daughter to live with him in the city. But he sent her back after a year. “Kharcha bahut ho raha that (it was too expensive)”, he says. Besides, he felt that if she got used to the city life, she wouldn’t like to go back to the village. Then, it will be difficult to get her married to a villager.

I ask Sasanth about his dreams for the future. “Expenses are so much there is no time to dream”, he relays. He has thought of expanding the business. “It will take around Rs. 3 lakh. I will start saving after 2–3 years. But tell, me who has seen tomorrow?” he smiles, looking away.

My T-shirt is soaked now. I insist on buying him a cold drink in exchange for his time. He folds his hands together. “Yeh hamari reet nahi hai (this is not our way)!”, he submits. I get up and take his leave, feeling very thirsty and very ashamed.

This research was developed as part of the Bharat Inclusion Initiative.