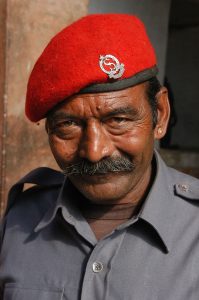

People of Bharat: Chandrabhan, Ahmedabad

“You see that there?” Chandrabhan says, pointing to a close circuit camera perched on top of a pole at a moderately busy intersection. “I have to stay within its range, else my supervisor will raise a complaint” he continues. He motions me to pull up a chair, so that I may be comfortable as we speak. As for him, he prefers to stay on his feet, in case a vehicle were to pass by.

It is a slow Friday morning in November. There is a slight nip in the air, but Chandrabhan and I have a spot in the sun. Chandrabhan works as a security guard on the premises of a neat and smart business park in Ahmedabad. Surrounded by tall facades of shiny reflective glass, Chandrabhan waits at his usual post, keeping a close eye for incoming visitors, about 100 metres from the main entrance of the complex.

He is a portly man with a gentle face. He hails a passing car, requests the driver to lower his window to enquire which way they are headed. In the exchange that follows, I see him lean on the car and gesticulate directions. He finishes off with a satisfied nod and walks back to his chair, where I am seated.

He knows the complex well, he has worked here for five years- since the time he moved to Ahmedabad from his village 80 kilometres away from the city. He tells me he is 55 years old and moved to the city with his family. Well, in a way, his wife and he followed their children, who had come to the city to attend college and had eventually settled into well-paying jobs.

“I was born, grew up, got married, raised my kids and spent the greater portion of my adult life in Kotnagar village. I am a village person. You see me here today, but to tell you the truth, I have always been a farmer really. That is who I truly am.” Chandrabhan reveals, with a look that assumes that I just could not have imagined it.

Chandrabhan Jatav has been a security guard for 21 years. He graduated from a college in his village in 1987 and spent over 7 years trying for openings in government jobs. He tells me that he passed five recruitment examinations for various openings under the central government, but unfortunately, none converted. “I passed the written examination for Lower Division Clerks (LDCs) three years in a row from 1987–1989. I would pass the written but fail the typing test.” he remembers. Once he figured out that typing was his weakest suit, Chandrabhan attempted recruitment exams that did not require that skill. He passed the examination for the office of an Upper Division Clerk (UDC) in income tax and central excise, but received no call for appointment. In the course of various other attempts at securing a ‘respectable’ job, Chandrabhan applied to a recruitment call from the Life Insurance Corporation of India (LIC) in 1993.

Those days the Employment News carried advertisements for LIC. The Corporation offered to recruit aspirants for a 90 day trial period as temporary assistants and promised to hire them on permanent basis for good performance. Chandrabhan recalls that his application was picked up by LIC. It was an exciting time. He liked the job and did well. In return for his commitment, local LIC agents retained him for a period longer than the stipulated 90 days. “What can I say,” Chandrabhan laughs, “I believe they liked my work. They kept me for a hundred and nineteen days. That is one, one, nine days! At the end of it, my Sir said that should I pass a written exam, they would take me on for good… that I would be an asset to them and that the Corporation needs people like me!”

Chandrabhan passed the exam and waited for the promised call. When none arrived, he followed up with his older supervisors to request help and guidance. As months passed, Chandrabhan’s patience wore thin. After a point, he decided to give up. His face strains as he revisits the struggle. “Nothing… I got no word from them, no matter how many chakkars (rounds) I made. So one day, I came back home, collected all my school, college, degree certificates, tied them up in a bundle and threw them into the back of the cupboard. The next day, I started working on the family farm.” For most of the next ten years, Chandrabhan devoted himself to his land. His family owned 12 bighas of land, where they cultivated cotton and jowar. This, he says, was before they built a canal in the village. Since the canal, cropping patterns have changed.

Nonetheless, Chandrabhan married, fathered three children- a son and two daughters, and supported his parents. “In the village, everyone is interested in your life. Everyone insists that one should have more than one child. They were always in my hair. My mother started to pray and observe vows, hoping my wife would conceive more babies. That is how we ended up with three kids.” Chandrabhan smiles and continues with some indulgence, “They are all grown up now and doing quite well. So, in a way, it all did work out.”

Chandrabhan started to work as a part time security guard in 2001. While earnings from the land were adequate for the family, he would often rake up his old desire to work for a ‘company’. “We had enough. In those days, if you owned some land and had Rs. 25,000 in savings, you could live a good life. But I kept applying for jobs.” He eventually stopped applying when his mother refused to let him leave the village to appear for an interview in Surat. “They were afraid, I was the only son. They were often ill and could not have managed by themselves. I realized that. So, I skipped the interview and found a small job with a security company within the village itself.”

Chandrabhan made Rs. 2700 each month for daily 12 hour shifts. They were in the village, so the income sufficed. As his parents passed and his children approached high school, Chandrabhan started to take an ardent interest in exploring career opportunities for them. He recollects that he was driven. He remembers, “I worked 12 hour night shifts and spent day times making sure my kids were on the right track. I would ask around to figure out good career paths for my children and guide them accordingly. I had learnt the hard way, there was no one to guide me in my youth. I experienced many hurdles and ended up being a night guard. But I wanted my children to do better. I wanted a better life for them. So I could not compromise on their education.”

All three of Chandrabhan’s children eventually moved to Ahmedabad after finishing school. His son earned degrees in software engineering and business management. Both his daughters graduated with degrees in science and proceeded to find good jobs.

Today, Chandrabhan has rented out his land to sharecroppers in the village. He receives one third of their net income from cultivation. “It is not a tribute or anything,” he clarifies. “They work on my land and pay rent. I do not interfere. I just like to be in the know of what is happening. They inform me when they start sowing, fertilizing or harvesting. I sometimes visit to supervise. The sharecropper takes care of everything else.”

Chandrabhan’s land yields two crops a year- paddy and wheat. Each season his share of earnings amount to Rs. 90,000 to Rs. 1 lakh. Back in Ahmedabad, he makes Rs. 15,000 per month from working as a security guard. He adds Rs. 10,000 from his salary to the household fund, leaves Rs. 2,500 in his bank account and retains the rest for his personal expenses. In all, between him and his son, Chandrabhan’s family has a monthly income of Rs. 38,000, which is just about sufficient to run the household.

Each month the family spends Rs. 10,000 on rent, Rs. 11,000 on EMIs, Rs. 9,000 on groceries and other essential supplies and Rs. 4–5,00 on utility bill payments. The family incurs two loan repayments- one for a personal loan they obtained for the wedding of their elder daughter and the other for a new laptop Chandrabhan’s son recently bought. As their utility bills appear a bit exorbitant, Chandrabhan explains that it is on account of the air conditioners at home. His son is used to air conditioners at his workplace and cannot do without them at home.

As he calculates his monthly income and expenditures, Chandrabhan confides that their finances get very tight by the 25th of each month. “We stretch ourselves as much as possible and wait for the month to end”, he says. Over all, the past three years have also appeared to strain his family’s finances. They spent close to Rs. 8 lakhs on their elder daughter’s wedding and on felicitating her new family on the birth of her first child. A ring ceremony for Chandrabhan’s younger daughter has also sizeably affected the family’s financial well-being.

Owing to the banks loans and relatively extravagant wedding expenses, Chandrabhan’s family has not been able to maintain much savings over the past three years. While Chandrabhan’s wife saves Rs. 2500 each month with a bachat mandal in their village, Chandrabhan is not keen on parking his money in fixed deposits or mutual funds or even on buying insurance. The returns are not adequate, he pronounces and proceeds to explain. “The interest rates have fallen and fallen. I have tried. I invested in the Kisan Vikas Patra earlier. It made your money double in 5 years. It was a very good scheme. But they have progressively cut the interest you earn from it, so investing there does not make sense anymore.”

“Consider even the fixed deposit (FD) schemes”, he challenges. “Compare the interest on FDs and the interest they charge on home loans. Home loans are so much more expensive. Say, if I were to park Rs. 50,000 in a FD, I will get Rs. 1 lakh when it matures in 10 years. Granted that my money will double, but Rs. 1 lakh will be worth less in 10 years than Rs. 50,000 is today!” Chandrabhan, however, does see value in mediclaim policies. He shares, “They reimburse the cost of medicines. That is useful. I had life insurance earlier. But it lapsed and I did not renew it. I don’t care how much money you pay out after I am gone. I am concerned with how you can help me today.”

Chandrabhan’s job as a security guard does not offer him much security for the future. “They can ask me to leave tomorrow if they like” he says. Moreover, in this line of work, a member of staff must work with a security agency for over ten years to be eligible for pension. Working at the business park for 5 years, Chandrabhan has witnessed a change of guard several times. The business park has terminated contracts with several security agencies, and while the management has changed, guards have remained the same. He explains, “See, the security agencies change and they don’t take us with them. If people think you are doing a decent job, incoming security agencies absorb you. We just change our uniforms and carry on. And after all this, they give you Rs. 1500 a month in pension if you manage to serve them for over 10 years. What are you going to do with Rs. 1500? Buy a cooking gas bottle this month and petrol for you motorbike the next?”

Despite his ongoing financial difficulties, Chandrabhan is not too fazed. He owns land and two houses back in the village. He is in good health- “haven’t had a fever since 2011!”,his children are doing well and overall, he is satisfied with how his life has turned out.

“We want to buy a house in the city” he says, as we wrap up. “My son is here, his work is here. We could all live together here if I could buy a house. That is what I am aiming for. Everything else will work out. People like me, we have been through a lot in life. We will make it through….whatever happens.”

This research was developed as part of the Bharat Inclusion Initiative.