How Trichy MSMEs came together to cut costs and find opportunities

Image by Justinvijesh via Wikimedia

For years, the fabrication cluster that had grown around the Trichy unit of the public sector behemoth Bharat Heavy Electricals had been following the same business model. Bhel was the main customer or the only customer for most of the small businesses. Bhel was set up by the government in the sixties to help boost the country’s power generation capacities; and its Trichy unit specialized in high pressure boilers. It did what a typical large public sector organization did during those times — it established a township for its employees at the outskirts of the town. It handheld its suppliers through the production process. It gave them the drawings, sourced raw materials, arranged for the transport, set the standards on how efficiently they have to use the materials, ceiling on wastage, etc. Its welding research institute conducts regular training to strengthen their skill base. The deal was simple. The suppliers should simply focus on their job related work.

And then, the market suddenly changed. Early in the last decade, Bhel’s rivals from the private sector started getting more aggressive. They tied up with global players and upped their game. One of the ways in which this competition manifested was the time it took to commission plants from the concept stage. While BHEL was taking as many as 63 months from concept to commissioning, the private players were doing it in 48 months.

Now, BHEL had to bring this down by at least 15 months. BHEL management felt that they could do that by cutting down bureaucracy, which was the biggest differentiator between the private sector and public sector. One of the things they did to cut the red tape was to put the procurement ball on the court of the suppliers. This fared as a challenge to the MSMEs in a few ways. They had built literally zero capacity for sourcing and procurement. BHEL said they will help them with a list of their suppliers. But, it was not the same. Individual businesses didn’t have the bargaining power. Even if they negotiated a good deal, transport was a problem because most steel suppliers were in central India. Sometimes their orders were lower than truck capacity, and tying up with other buyers who could share the trucks with them was a pain.

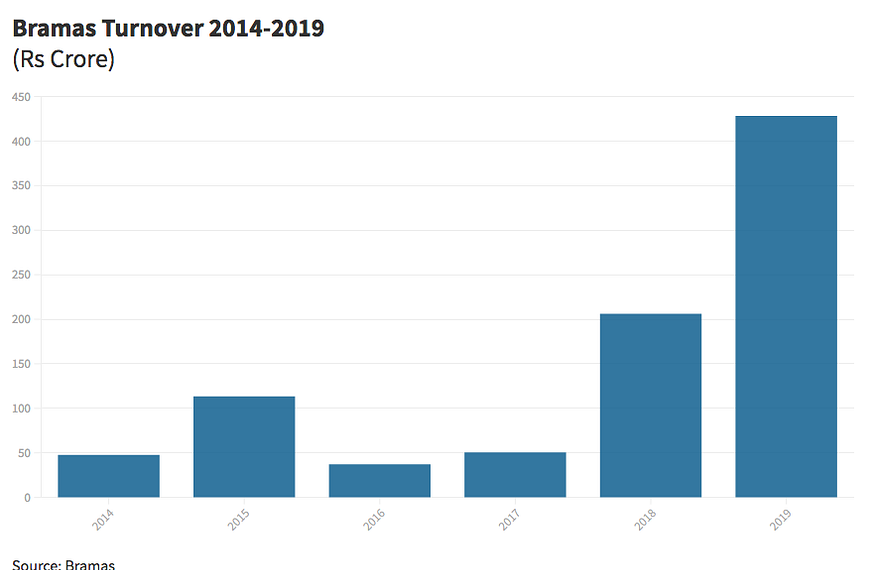

Then they came up with an interesting solution. In late 2013, BHELSIA (BHEL Small and Medium Industries’ Association), a group of around 400 small businesses supplying to BHEL, got together to form a section 25 company (non-profit) called Bramas Industrial Service Association. Bramas achieved what the small businesses couldn’t achieve independently. Bramas quickly assembled the skills needed to procure materials. Since they were aggregating the orders, they had bargaining power. The aggregation also gave them economies of scale, and logistics became more efficient. All these resulted in bringing down costs. However, the most interesting consequence was now these businesses can reduce their dependence on BHEL, and can look at other customers.

This research was developed as part of the Bharat Inclusion Research Fellowship.