FPOs and Bharat’s Funding Ecosystem

Image by Amitali on Shutterstock

RBI recently came out with revised guidelines to elaborate Priority Sector Lending (PSL). It is an attempt to align PSL better with emerging national priorities and bring ‘sharper focus on inclusive development’. Lending to the agricultural sector (traditional, infrastructure and ancillary services) has been top priority for the past few years. As the only bright spot and performing sector during this challenging period, we thought it would be apt to look into this sector in a bit more detail.

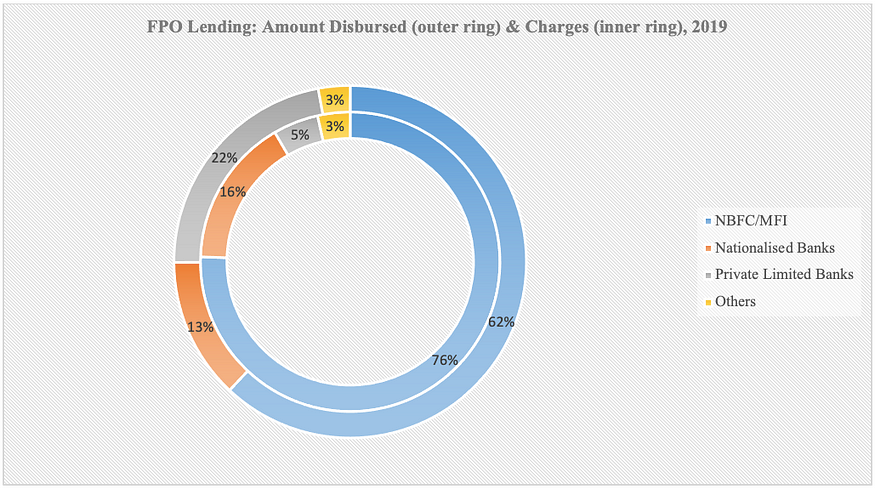

The credit absorption capacity of the FPO market for the year 2019–20 is estimated to be close to INR 1000 Crore[1]. For the FY 2019–20, the loan disbursed for the sector has been over INR 57 crore. Data from primary and secondary sources indicate that only 13 % of the loan amount disbursed originated from nationalized banks (see figure below). More than 75 % of the loan disbursement in this sector has been through non-banking finance companies (NBFCs) or micro-finance institutions (MFIs). Despite incentives and policies only a few nationalised banks have ventured into lending to FPOs.

Source: Adapted from Ministry of Corporate Affairs (MCA) Database

Let’s look into the factors responsible for this phenomenon. One of the most important parameters for financing institutes is the charge size (loan size). As a convention (which is very random), any loan amount less than INR 10 million is treated as small. Nationalised banks generally do not prefer to lend money to FPOs for a lesser amount. On the other hand, NBFCs are agile enough to develop Agri-focused financial products and services. However, this facility comes with a heavy premium. The interest rates charged by them is humongous and does have an impact on the profitability of the FPOs (especially the ones dealing with longer shelf life products). From our interactions with a few FPOs across the country we also realized some deeper problems. In a couple of instances, the CEO of the FPO had to educate the branch manager of the FPO’s legitimacy as a legal entity. Many a time, the field staff of the banks are not aware of the FPOs and their functionality. This indicates that there have been no specific bank level corporate guidelines to assist the branches and the field staff!

FPO financing is a large market, but the absence of big players such as nationalised banks indicates the following issues. First and foremost is the lacuna/incapability of the FPOs to demand large loan amounts. Second is the inadequate visibility into FPO’s operational and financial health creating an air of doubt on their bankability. Though the impetus from the RBI is well intended, in the absence of tools that can benchmark and monitor FPO’s operational and financial prowess (specially cash flow), the management of financial institutions will be unwilling to venture into the sector. Third, training of bank managers to design products for the rural is critical: as depending on geography and crop, the cash flow fluctuates and requires a tailored loan repayment mechanism. It is not enough to boost the formation process of producer organisations; it is equally (or perhaps even more) important to ensure a supportive ecosystem for them to thrive. The devil always lies in the implementation! When nationalised banks have not been completely aligned with the government’s development agenda, is it possible to dream of a financially inclusive rural India?

References

RBI Priority Sector Lending Guidelines, Sept 2020

2. Caspian Impact Investment Advisors Pvt Ltd. (2019). Guidebook on Lending to Farmer Producer Organisations.

This research was developed as part of the Bharat Inclusion Research Fellowship.