Data Ownership and the Policy Environment

Image by thodonal88 on ShutterStock

As we continue our primary research by interviewing workers of the digital platforms to understand the impact of data locked within big ‘gig economy’ platforms (lesser bargaining power, inability to access financial services, upward mobility bottlenecks etc) it’s important to understand the other side of the coin, the State. In this blog we’ll have a quick look at European Union’s (EU), General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), India’s Personal Data Protection Bill (PDPB) — from a data ownership and portability perspective and what an ideal solution platform might look like.

PDBP vs. GDPR (Data Ownership & Portability POV)

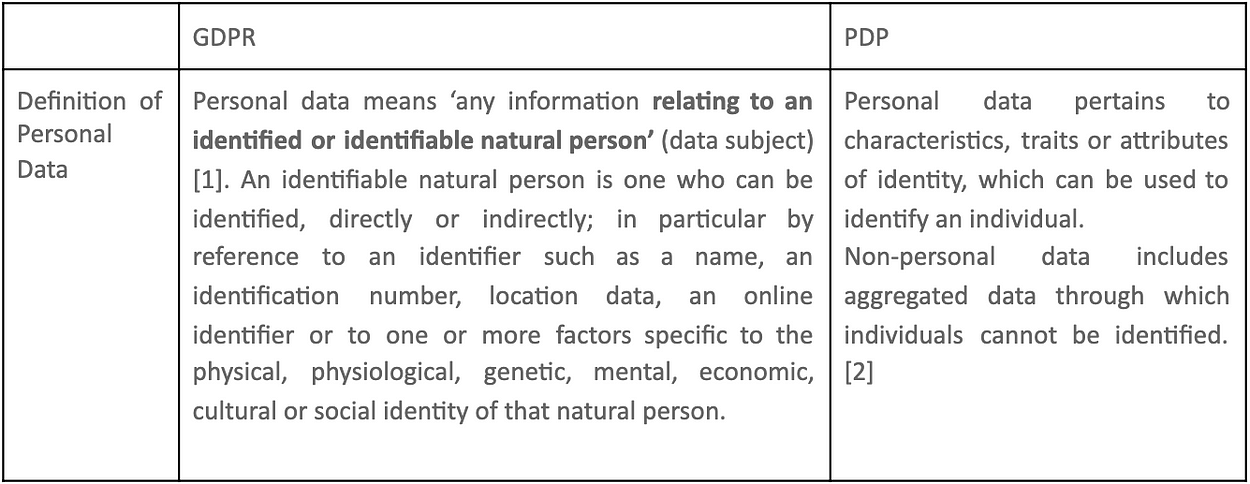

Data is broadly defined as the information in digital form that can be transmitted or processed, by the Webster’s dictionary. Data can be broadly classified as personal and non-personal data. The concept of Personal Data is at the heart of data protection regulations like the EU’s GDPR & India’s PDPB, 2019.

GDPR regulation focuses primarily on any information relating to an identified or identifiable entity. In this context, an identifier could be a name, location, genetic, mental or economic identity of the person. A breach of failing to respect GDPR norms in the EU can result in a fine of up to 40% of global turnover or EUR 20 Million, whichever is greater. Firms from the United States engaging with the EU however have the ability to register themselves for the EU-US Privacy Shield. In essence it allows businesses from the US to avoid fines unless they knowingly violate Federal Trade Commission requirements in the United States. GDPR’s functional focus is on the data of the individual and the people who access it. In the same vein, data portability in the structure of GDPR is heavily reliant on the individual’s willingness to provide access to their data. It is structured around EU focus on privacy and the right to be forgotten by digital platforms if the individual decides on it.

In India, the Data Privacy Bill (PDPB) of 2019 [3] has been the leading regulation when it comes to privacy. The PDP focuses on splitting constituents in a data based interaction into the individual and “data fiduciaries”. The PDP structurally focuses on storage of sensitive data within national boundaries. It has provisions for individual data to be accessed by a third party without consent in very specific instances. The core focus of the PDP is not to restrict enterprise access to personal data but rather to structure limits on how and where data is accessed, stored and processed. The bill has provisions for individuals to access records on cases where their personal data was processed. The key loophole with the PDPB is likely that it does not protect the byproducts of services provided by a data controller. This could be algorithmic assessments made by a third party without individual consent.

The implicit assumption underlying these relatively new regulations is that the cat is already out of the bag so to speak, and data exchange between you and another party will occur (if it hasn’t already). Once you share your data, provisions governing its downstream use and security are in place for your protection if you live in a regulated jurisdiction. Since you are ‘considered’ the owner of the data, you can choose to withdraw a company’s right to use it at any time. In this way, data ownership is conceptually better for data privacy than the previous approach, which was much more of a free-for-all and entirely dependent on how companies wanted to present privacy options to their users or not. [4]

However, it’s important to understand that data ownership and privacy are not one and the same. The difference is nuanced — Privacy requires us to at least conceptually agree, that you as the data subject own your data and the data you generate. Data ownership in itself does not necessitate that privacy be respected by default. This goes down to a more fundamental question of what kind of economic good is data? Economists have no questions about the rivalry of data (data is non-rivalrous) but when it comes to excludability this is where the state and the markets are in loggerheads.

In a paper titled Nonrivalry and the Economics of Data, by Stanford Economists Charles I. Jones, Christopher Tonetti an ideal data marketplace is discussed. [5] An excerpt of that below:

“How do you balance concerns over privacy, competition, and efficiency when considering a market for data? To answer this question, Jones and Tonetti started by modeling an optimal economy managed by a benevolent dictator who respects all of the variables in play. This scenario was used as a benchmark of what it looks like to maximize welfare.” [6]

Against this ideal, they then tested three scenarios conceivable in today’s world: Companies own data, people own data, or the sharing of data is essentially outlawed. In the first case, which most closely resembles today’s market, companies neither respected consumer privacy as much as consumers wanted nor shared effectively with other companies. But instead, when individuals owned their data, Jones and Tonetti found outcomes that were close to optimal. ‘Consumers care about privacy, but they care about consumption, too,’ says Jones. With this split incentive, consumers preserved the data they wanted private but sold other data to many different firms, capitalizing on the value inherent in sharing nonrival data widely.

The third case in which sharing of data was banned, unearthed an important insight directly relevant to the real world: Failing to share data ultimately stifled economic growth. Legislation around how to regulate data therefore concerns not only issues of privacy but also the long-term health of the economy.

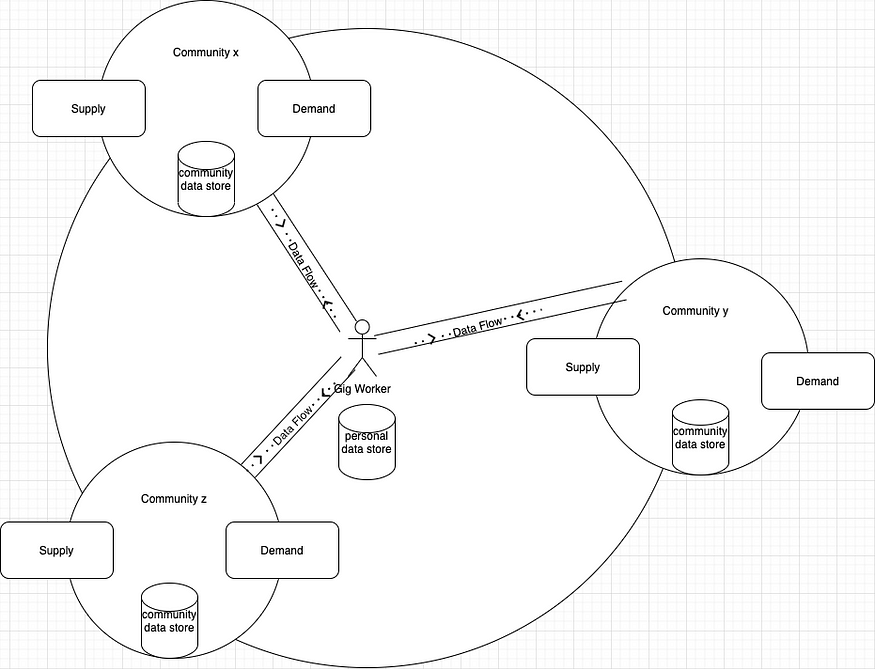

So an ideal data marketplace would be where the data principle / individuals own their data and there’s incentives for them to share their non-rivalrous data. This is in alignment with our earlier envisioned model of a community-based economy where the gig worker still owns their data but being part of the community makes sure there are incentives being set to share the transaction (in our case, skill transactions such as upskilling, re-skilling, gigs etc) data.

Looking beyond the Gig Economy [7]

Imagine every circle you see here as a node and suddenly it looks very familiar in terms of a technology architecture which is a distributed network with distributed consensus in place. New age technologies such as blockchain and quantum cryptography make it really possible to make sure ownership is maintained at a data principle level. In order for data ownership to be effective in safeguarding data privacy, some argue it must follow an opt-in regime framework, [8] where data collection does not occur without affirmative consent from the data subject.

Now that Ownership is addressed, we got to address the usage of this hard owned ‘data’. Not everyone knows how to put their data to use. Hence the role of communities as data fiduciaries becomes important.

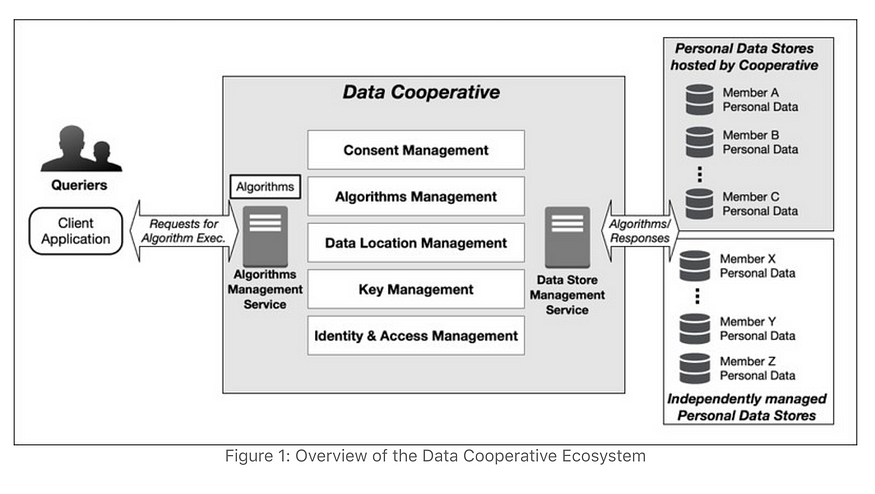

The key aspects of the data cooperative/community

- Individual members own and control their personal data [9]

- Fiduciary obligations to members: The data cooperative has a legal fiduciary obligation first and foremost to its members [10]. The organisation is member-owned and member-run, and it must be governed by rules (bylaws) agreed to by all the members.

- Direct benefit to members: The goal of the data cooperative is to benefit its members first and foremost. The goal is not to ‘monetise’ their data, but instead to perform on-going analytics to understand the needs of the members better and to share insights among the members. [11]

Thus a community not only gives a sense of belonging, increases bargaining power and improves the social capital of the individual (gig worker) but also takes on the role of a data custodian, in the long winding fight against the big-tech data-centralized monopolies.

References:

[1] https://gdpr-info.eu/

[2] https://yourstory.com/2020/10/comparative-study-data-privacy-laws-pdpb-gdpr-ccpa

[3] https://www.prsindia.org/billtrack/personal-data-protection-bill-2019

[4] Why Data Ownership isn’t Privacy but better than the alternative — Lauren Kaufman https://medium.com/popular-privacy/why-data-ownership-isnt-privacy-6eb69355aae7

[5] Nonrivalry and the Economics of Data By Charles I. Jones, Christopher Tonetti — https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/faculty-research/working-papers/nonrivalry-economics-data

[6] How much is your private data worth and who should own it ? — https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/how-much-your-private-data-worth-who-should-own-it

[7] Looking beyond the gig economy — Joel & Moses — https://insights.iimaventures.com/works/looking-beyond-the-gig-economy/

[8] Opt in , Opt out — Lauren Kaufman — https://medium.com/popular-privacy/to-opt-in-or-opt-out-5f14a10bae24

[9] Y. A. de Montjoye, E. Shmueli, S. Wang, and A. Pentland, “openPDS: Protecting the Privacy of Metadata through SafeAnswers,” PLoS ONE 9(7), pp. 13–18, July 2014, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0098790

[10]Roles of a data cooperative: J. M. Balkin, “Information Fiduciaries and the First Amendment,” UC Davis Law Review, vol. 49, no. 4, pp. 1183–1234, April 2016.

[11]Data Cooperatives by Alex Pentland and Thomas Hardjono Apr 2020 — https://wip.mitpress.mit.edu/pub/pnxgvubq/release/1

This research was developed as part of the Bharat Inclusion Research Fellowship.