How do slum dwellers borrow?

Photo by Santhosh Varghese on Shutterstock

Imagine if a person came on her/his feet or on her/his two-wheeler and offered you credit in way that seems inexpensive and customized. The lender is also able to sympathize and act as a life coach to your financial problems. Now imagine this to be a lived reality for a substantial number of households who live in shanties in Chennai and each of them are approached by 20–25 such ‘cash peddlers’ on a daily basis. It’s the perfect market for quick cash, advertised by frequent visits by the lenders and diffusion of information through word-of-mouth.

Borrowers tend to use these loans for immediate to medium-term consumption and productive purposes. There could be variability in the utilization of the loan depending on the household’s occupational profile, family structure, income, and asset levels along with the mental make-up of the users.

In our ongoing fieldwork in the slums of Chennai, loans from friends and family members, moneylenders, chit funds and pawn-brokers far surpassed the loans borrowed from MFIs or other formal sources. It is interesting to unpack this phenomenon and understand what could be driving the need for informal finance even in the presence of formal financial institutions.

Credit or Immediate Liquidity?

For many households, low to medium value credit is used as a quick substitute for unsteady earnings. For instance, Sudha (name changed) runs a single woman headed household. She works at a construction site and earns daily wages of approximately INR 400 per day. Since construction work is available only 18–20 days a month, her monthly salary totals to about INR 8000. Sudha has two daughters who are married, with children. Sudha’s husband left her to fend for herself and she has no access to any social insurance in the form of alimony or pension. Her daughters are also unable to help her financially.

Sudha significantly relies on thandal*[i] loans, moneylenders, pawn-brokers for small ticket loans in the range of INR 2,000–15,000. At the time of the survey, she had three loans from moneylenders and 7–8 petty thandal loans on a rolling basis. Sudha uses these loans for both, consumption and production purposes. Some of these are also transferred to her daughter when she needs money on account of her children’s sickness.

Typically, these loans carry an interest of about 15% per month. When asked about repayment, Sudha reveals that she cannot repay most loans on time because of insufficient funds. But, the humiliation attached with defaulting on a loan does not worry her as much as losing access to credit because of non-repayment.

Photo of the slum in which Sudha has been residing for more than 30 years; Chennai, 2019

Sudha’s situation raises certain questions about the financial health of her household. With little or no savings, a plot of land in her village (that she plans to sell during her old-age), Sudha uses informal credit as a near-substitute for liquid cash. It is difficult to comprehend how she manages multiple loans and independently copes with threats from moneylenders.

The risks and vulnerabilities faced by Sudha do not depict a standalone case. During the course of my fieldwork I frequently came across households with multiple loans from informal sources coupled with a few loans from MFIs, reflecting the scale and magnitude of this issue. Experiences of Sudha (and many others) make me wonder whether there is a code of conduct for local moneylenders and if their interest rates are capped at a certain market determined rate. I also got curious about the regulations around moneylending in the country.

Existing legal framework for moneylending

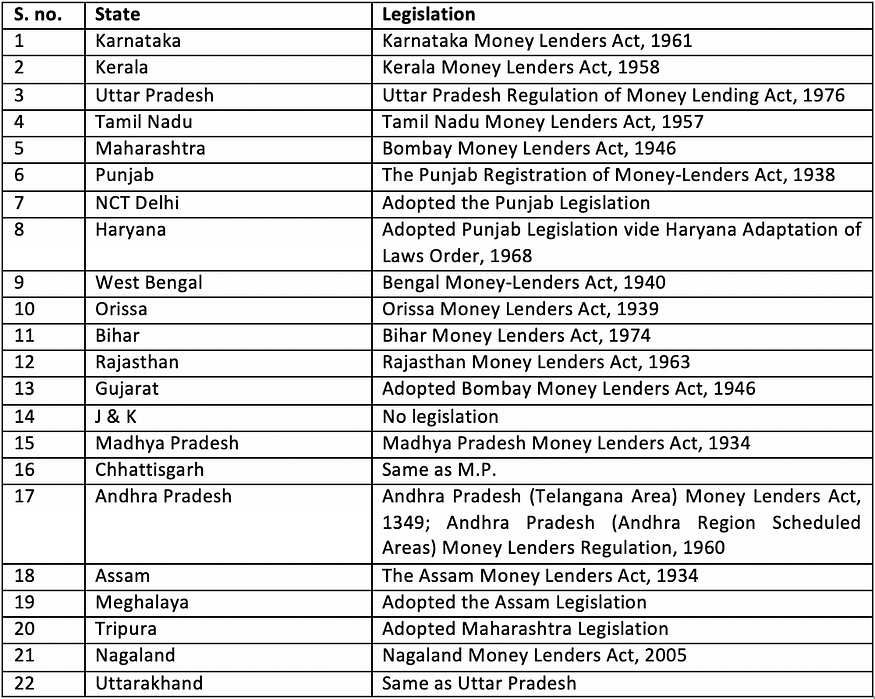

The seventh schedule of Constitution of India has conferred the power to legislate on the matters of moneylending and moneylenders to the respective States. Majority of the state legislations in this regard were passed decades ago (see table below). No points for guessing that many have not been amended or updated over time.

Some of the salient components of moneylending legislations are –

1. Registration/ licensing of moneylenders

2. Keeping, filing and furnishing of accounts

3. Interest rates either fixed by Statute or the Statutes empower the respective Governments to decide the rates

4. Provision against violence/ intimidation/ molestation of debtor or debtor’s family members

5. Other state specific provisions

Despite having a well laid out (albeit dated) legislation in place, it is important to recognise the difficulties in enforcing these legislations and create awareness about the ground realities of the moneylending business in different states.

A survey conducted by the Reserve Bank of India in 2007, found that moneylenders often operated covertly without holding a valid license. Some of the salient reasons behind ineffective implementation of the Act included lack of adequate administrative infrastructure, lack of awareness about the provisions of the Act, absence of complaints, interference of political leaders, and inadequate guidelines.

In Tamil Nadu specifically, moneylenders are regulated under the purview of two legislative Acts. These are the Tamil Nadu Money Lenders Act (1957) and the Tamil Nadu Prohibition of Charging Exorbitant Interest Act (2003). Among other regulations, these Acts prohibit lenders from charging usurious interest rates. However, in my current field experience, there are few lenders who are registered or operate within the purview of these legislations. I also find illegal moneylending businesses, operating on trust, convenience and proximity between the borrowers and lenders. However, the business is not legitimate. In case of delinquency or default neither of the parties can seek legal remedy. In this case the lender either resorts to abusive methods of collection or the borrowers repay through new credit and eventually subjecting themselves to vicious cycles of over-indebtedness.

This brings us to an interesting question — does the solution to informal moneylending market lies in substituting them with institutional agencies or in licensing moneylenders and creating linkages between them and the formal lenders.

In part two of this blog, we will take these up in detail.

Endnote

[i] A thandal loan is a short-term, informal credit product. Per my field experience, the loan amounts range from Rs.2000 to Rs.75,000 and the loan tenure could be anything between a couple of days to a few weeks, but typically less than a year. The lender deducts the processing fee and some interest amount from the loan at the time of disbursal. The interest rates range from 3–5% per day to 20–30% per month depending on the loan amount, tenure and whether a collateral backs the loan. Repayments periods vary across daily, weekly, monthly cycles.

This research was developed as part of the Bharat Inclusion Research Fellowship.