Decoding Financial Lives of Urban Poor

“It seemed to him that in [urban slums], fortunes derived not just from what people did, or how well they did it, but from the accidents and catastrophes they dodged. A decent life was the train that hadn’t hit you, the slumlord you hadn’t offended, the malaria you hadn’t caught.”

― Katherine Boo, Behind the Beautiful Forevers: Life, Death, and Hope in a Mumbai Undercity

In countries experiencing rapid urbanization and burgeoning cities, slums are generally regarded as a strong negative externality. As on 2011[1] India was home to 1.37 crore households in notified[2] and non-notified slums[3] across 12 states; often these slums are seen as a breeding ground for urban poverty and the resulting squalor. Urban poverty, as we understand is a multidimensional problem that extends beyond low income to low levels of human, social, physical and financial capital. In the past few years, slums in India have received considerable attention with regard to better housing and sanitation policies. However, there is a parallel growing need to also have an in-depth understanding of the financial lives of urban poor households for effective identification of missed opportunities in developing a targeted financial market.

Typically, policies directed towards achieving financial inclusion in India are either focussed on serving the rural population or are agnostic to the end customer. Since late 1960s financial inclusion initiatives in India have taken shape through various mandates, innovative channels and specialized products targeting the unbanked and under-banked segments. Some of these pan-India initiatives included setting up of rural regional banks, non-banking financial companies and small finance banks, fixing of priority sector lending targets, introduction of banking correspondents for enabling low-cost last-mile delivery, and introduction of no-frills bank accounts among others. These policies were geared towards the singular motto of serving the poor through universal access to financial products and services. However, a blind spot for these policies has been their inadvertent lack of attention towards improving the financial portfolios of urban poor families living on the fringes of developed cities.

Theoretically speaking, urban poor households do not lack ‘physical access’ to financial institutions. Yet, as on 2011, out of 1.37 crore slum households in India only 53% had ever interacted with formal financial markets[4].

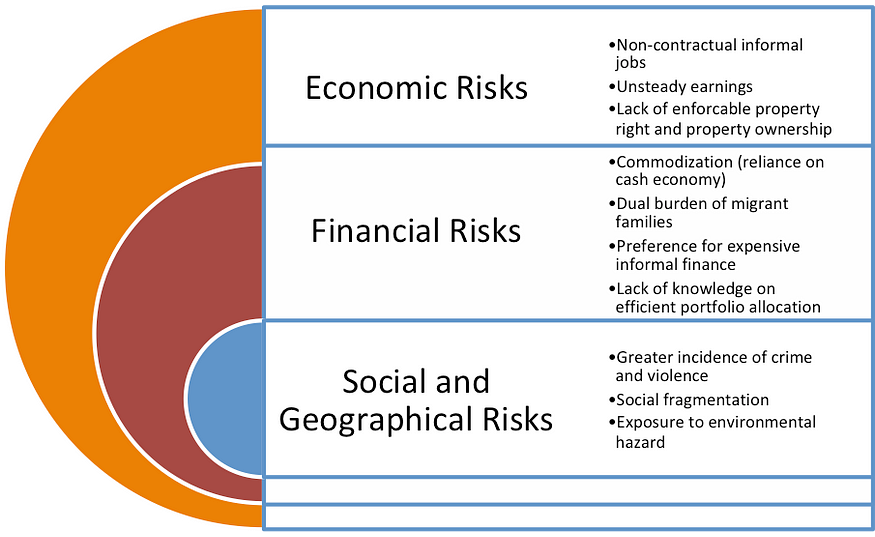

A prudent starting point to serve this segment of the population would be to first understand the fabric of urban poverty. Households within slum areas are subject to economic, financial, social, and geographical risks (see figure). The unique set of vulnerabilities that differentiates them from the rural poor emanate from low monetizable skill sets, idiosyncratic risks to income due to uncertain job markets, and constrained accumulation of physical assets. Considering these differences, one finds that there is a substantial theoretical gap in India with respect to understanding and contextualizing the heterogeneous financial lives of the urban poor.

Therefore, to bridge this gap and to systematically understand the financial lives of urban poor households residing in slums, I aim to conduct an in-depth examination of physical and financial assets, formal and informal debts, income and cash flow volatilities, risk management techniques, coping mechanisms, financial goals and preferences of urban poor households.

I aim to capture a holistic view of the finances of the household. I will use financial diaries of said households for high-frequency collection of data with an aim of constructing a balance sheet and cash flow statement of each household. The advantage of collecting this information will be twofold — (a) it will help us understand the financial wellbeing of urban poor households, and (b) it will highlight the gaps between financial needs of these households and existing financial products currently being available to these households.

Financial diary, as survey instrument, allows for closely observing the movement of money in and out of households and identifying the dips and spikes in cash flows. This methodology also effectively captures the cost borne by households in accessing basic services like water, electricity, rent and other high volume transactional expenses.

A slum dwelling household’s exposure to vulnerabilities ranges from constrained access to basic services like water and electricity to heavy dependence on exploitative informal markets for goods, services and finances. Moreover, not all slum households are alike; the slum population in India is highly heterogeneous. Each slum could be diverse along sectarian, religious, linguistic, occupational, and political lines. In this milieu, my study aims to closely observe and recognize the financial habits and choices of slum-based households sharing a common string of vulnerabilities, challenges, opportunities and indigenously devised coping mechanisms.

Finance as a tool is incrementally beneficial for the poor when it helps them move limited resources over their lifetimes and through different stages of their lives. Currently, many formal financial products (with the exception of microcredit) that are secure, affordable, and convenient are targeted to fulfil needs of wealthy families earning steady salaries. This leaves behind the economically vulnerable households with volatile incomes living in geographically disadvantaged pockets.

Financial institutions (FIs) are an integral part of fuelling progress in cities. However, their capacity to deliver to heterogeneous segments of population is constrained by range of management, political and cost issues. Increasingly, FIs are required to explore different approaches to create inclusive service delivery models that are affordable and scalable. To experiment with new approaches of service delivery, new types of information points are required. This study is a step in that direction, in the hope of creating more inclusive financial systems that work for all segments of poor.

References

[1]Census 2011

[2]As per NSSO (2012) Urban slum census — Areas notified as slums by the concerned municipalities, corporations, local bodies or development authorities were termed notified slums

[3]As per NSSO (2012) Urban slum census — Any compact settlement with a collection of poorly built tenements, mostly of temporary nature, crowded together, usually with inadequate sanitary and drinking water facilities in unhygienic conditions, was considered a slum by the survey, with minimum 20 households

[4]Urban Slums in India, NSSO 69th Rounds, 2014